Homelessness in Grand Haven

April 13, 2017

Staff editorial

Grand Haven is a bubble. We’ve heard it many times before, from teachers, parents and friends. We’re sheltered, homogeneous and privileged. We’ve been told time and time again that it’s easy for us to turn our backs on what is happening outside of this high school.

We knew all of this to be true.

And yet, when we, as a staff, found out that last year, there were 216 homeless kids in GHAPS, we were shocked. We felt blind, upset. We asked ourselves, “How didn’t we know this? How could we have missed the statistics right in front of our faces?”

The answer is simple: it’s easier to pretend that troubling situations aren’t there, rather than seek out information that confirms them.

We don’t hear about our fellow 187 students without homes this year because it’s not something people want to talk about. Because we don’t want to talk about it, a stigma is created and upheld. And because that stigma exists, the victims of circumstance stay silent.

The teens that hop from couch to couch because their parents kicked them out don’t want to be singled out, even though youth of the ages 12-17 are more likely to be homeless than any other age group.

The families that get evicted because 45 percent of people in Grand Haven report struggling with paying for expensive housing don’t seek help because they’re afraid of labels, afraid of a world that calls those who need assistance “lazy” or tells them to stop relying on “handouts.”

It’s a vicious cycle of ignorance, judgement and fear that creates the very bubble Grand Haven is surrounded by.

As young people, as privileged individual and as game-changers, the Bucs’ Blade believes that it’s our job to pop that bubble.

We talked about it before in our Pay It Forward paper last year, we have a call to action in all of our letters and staff-eds. But this time, we wanted to show students exactly what is outside the box of Grand Haven.

This edition’s in-depth is a collection of profiles about people who have been homeless, including two current students and two alumi. We also introduce you to a teacher who has dedicated his time to helping those in need. You’ll read about staff members who work to aid students and families experiencing homelessness.

We hope that in hearing their stories, your idea of homelessness will be changed. We hope that you will share what you read with your friends, and look upon those without homes without a predetermined stigma. We hope that you will develop empathy, and most of all, we hope that you will be inspired to help.

Because, as always, the Bucs’ Blade believes that taking action is always the best solution. We have provided a list of volunteer or donation opportunities as well as places to call for help in place of our letter, on page 3. We also will be posting information about what we, as a staff, will be participating in as our upcoming service project.

Only when we work together to step outside of our comfort zones will that so-called box truly be broken.

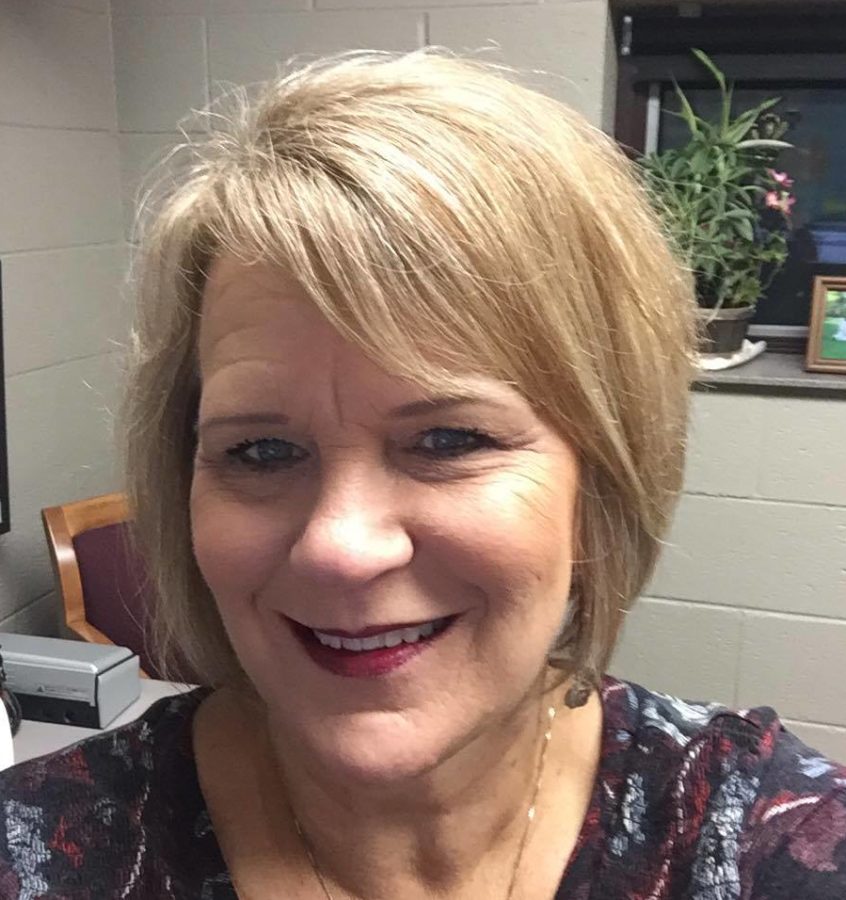

Cindy Benson: The Connection

A sharp ring echos through the office, bouncing off of walls covered in framed family photos. Grand Haven Area Public Schools (GHAPS) Homeless Liaison, Cindy Benson, swivels in her chair and answers the phone, grabbing some loose paper next to her to take notes. She jots down a phone number, names and various details and thanks the caller. Then, she gets to work.

She has a new client.

Benson has been working with homeless students for six years, and services children in grades preschool to 12, as long as they are in GHAPS. Every school district is required to have a homeless liaison, and it’s usually someone who holds another job in the system. Benson is also the GHAPS Information Services Specialist. According to her, homelessness is supposed to take up about five percent of her time, but because the cases are plentiful, diverse and incredibly important, it takes up more like 40 percent.

“When you start to talk about families and homelessness, they look like you and I, however, we’ve got families that live in cars,” Benson said. “And because we have the community that we are, we have families that live in tents, that live in campers, and families that live in shelters.”

Many of these families have young children in the area’s public schools. That’s where Benson comes in. She serves as the primary link between GHAPS and homeless students, finding ways to create a stable environment. Often times, school serves as that a large factor for that security.

“It’s a place that they can come that they know they will be warm, they will be fed, they will be dry, their needs will be met,” Benson said of the school environment. “Things are consistent. They’re in the same classes with the same kids with the same teachers, they have the same administrators. It’s just more about consistency. The number one role is to make kids that are going through trauma, to make school a safe place for them.”

But because they wish to fit in and are often facing physical and emotional instability, Benson says their first reaction is to turn away from help. Teenagers and adults alike commonly remain under the radar, embarrassed about their situation.

“There’s a fear of, ‘Oh my goodness, everyone is going to know,’” Benson said. “So, they try to keep it private. But there’s also a fear of, ‘How am I going to eat? How am I going to get clothes? How am I going to get my homework done?’”

Those concerns are heightened when the misconceptions and lack of information are factored in as well. In a recent survey by the Bucs’ Blade, 41 percent of students said they were unsure if homelessness is a problem in the area, while 36 percent it wasn’t at all.

It’s not our norm, it’s not what people expect in our community, so we need to break that bubble, break that box.

— Cindy Benson

“When you think of homelessness you think of everything that you see and hear about in movies or what you see on television, and that’s not what our homeless population looks like,” Benson said. “I can tell you stories about kids that are current students right now, that are homeless teenagers because their moms are heroin addicts. That’s here. That’s in Grand Haven. These kids chose to walk away from that situation because they wanted better for themselves. But that’s here, and we just don’t see it. It’s not our norm, it’s not what people expect in our community, so we need to break that bubble, break that box.”

However, she usually faces disbelief when explaining to administrators or citizens that last year, there were 218 homeless kids in GHAPS.

“When you say those things, people are like, ‘Wait what? How can that be? We live in Grand Haven, everyone has what they want, it’s a beautiful place!’” Benson said. “Well, it is. But it’s also a sad place for some folks.”

According to Benson, costly housing is the main cause of homelessness in the Tri-Cities area. A 2016 study by the United Way reported that 45 percent of people living in Grand Haven struggle with housing costs.

“Its an expensive place to live,” Benson said. “We have great schools and so they’re torn between, ‘Do I give my kids the best I possibly can and the best chance by letting them have the best opportunity to rise to the top to achieve their goals, or do we go to the north or the south where housing is a bit cheaper but the schools aren’t necessarily as great?’”

As the area’s homeless liaison, Benson doesn’t just focus on housing and schooling. She works to teach individuals how to be self-sufficient, give them options and help them find resources.

“So many of these families, no one has ever stood by them,” Benson said. “No one has ever given them boundaries. No one has ever taught them how to grocery shop to sustain their family, so it’s standing by them, teaching them, restoring their dignity and their faith in the humanity of our society and just helping them and telling them, ‘It’s okay to fall, you’re gonna fall. You’re gonna fall backwards. You might lapse, but we’re here to help you and pick up the pieces.’”

A sign hangs above Cindy Benson’s office.

Although her main job is to find ways to physically help her client, Benson realizes that creating empathy is also a necessity to help the homeless.

“I want people to react,” Benson said. “I want them to feel something. That’s my number one goal, just feel something, have an emotion that is attached to this. Care about other human beings who are not the same as you.”

That care is typically expressed through donations, monetary and material. Benson says she graciously accepts any gifts to the department, and if she can’t use it, another local shelter will. She also notes that simply supporting families and individuals is productive as well.

“Whether it’s a teenager, a family, a mom or dad or whatever, just by talking to them and letting them know that you care and letting them know that it doesn’t matter how they got this one spot in their life, nothing back there matters,” Benson said. “We just want to take each day as one point in time and move forward.”

She also aims to help students succeed in the long run, which is why she personally goes to the laundromat teaches them how to wash clothes, shows families how to grocery shop and advises individuals on financial decisions. She says she isn’t afraid to be tough and strict because she knows she is setting each case up for future prosperity.

“Homelessness isn’t just a tick in time,” Benson said. “It’s something we have to help them get through, help them get out of.”

Q&A with Kayleigh

22-year-old Kayleigh is from North Muskegon, but she spends some of her time standing on the corner of Robbins Road and South Beacon Boulevard. We asked some questions about what it’s like to ask for help from the side of the street, and this is what she told us.

Q: How long have you been out here today?

A: Well…it’s 4:30 now…I’m pretty sure I got here around 1:30 so, like, three hours?

Q: Why come to Grand Haven if you live in North Muskegon?

A: I’m kind of embarrassed. I don’t want to see people that I know.

Q: How do you feel when cars just drive past you?

A: Ashamed. I feel invisible, like I don’t matter as much as everyone else.

Q: What about when people stop and offer some help?

A: It feels really good. I feel like I’m a human being again.

Q: Do you think standing out here is an effective way to reach the goals that you have or get the things you’re asking for?

A: I’ve been trying to get a job, actually since May, it’s just that now we have a shut off notice so I need the help now. I didn’t know what else to do. In the Bible it says to ask and you will receive so I thought, ‘Okay, I’ll go ask then.’

Brittany Vandoorne: The Realist

WORKING HARD: Vandoorne smiles while she hostesses at the Kirby House. She has worked there for around a year, saving money for housing and, hopefully, college. She says she has struggled to find a job, since she has to fight against the stigmas of disability and homelessness.

While most 20-year-olds are thinking about what to do when they graduate college, Brittany Vandoorne, a 2014 GHHS graduate, is worrying about where she will be living in next two months.

She currently lives with three roommates in a seasonal rental downtown Grand Haven, just a short walk away from where she works.

“I’m supposed to be out in May,” Vandoorne said of her current residence. “I don’t know where I’m going to go next.”

This isn’t the first time she’s been unaware of what her living situation will change to.

Vandoorne has been homeless for two years.

She was adopted from her birth parents by her aunt and uncle when she was 11. According to Vandoorne, her parents were poor, but chose to spend what little money they had on drugs and alcohol instead of caring for their children. Her aunt and uncle raised her until she was forced to move out for repeatedly breaking family rules.

According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, individuals aged 12 to 17 are more at risk of being homeless than other age groups. Vandoorne was 18.

She then lived with her grandparents for several months before moving to the Hope House, a homeless shelter run by Love In Action. It houses women and children, but men are moved to the Harbor Hall, a program also serviced by Love In Action. An application is required to be accepted into the shelter.

Vandoorne says she was suffering from depression during the time and eventually was removed from the home after three months.

“I was kind of brand new to the homeless thing so I was depressed, I didn’t really want to be in the world and I didn’t want anything to do with anybody,” Vandoorne said. “I was mad at myself for making a mistake that cause me to get kicked out of my parents’ house. I was always hidden. But living there was actually pretty good for me because I was under a roof with bedding with blankets with food. There was a point where I got kicked out because I was having suicidal thoughts and they wanted me to get help.”

Vandoorne stayed at a hospital for two weeks because of her mental health. Desperate for release, she called her friend Kate, who took Vandoorne into her home for four months. With the help of Kate and her parents, Vandoorne was able to finally find a job at a local restaurant, the Kirby House, where she still works. However, she believes that getting hired was one of the toughest obstacles she faced because of the misconceptions some have about homeless individuals.

“I guess just to people, homeless people don’t work hard.” Vandoorne said. “That’s just what people put in their minds. Before I was homeless I was that kind of person too. I would look at a homeless person and think, ‘You could totally just get a job,’ but now I see where they’re coming from.”

Not only did she have to deal with the stigmas of being homeless, but Vandoorne also had to fight to prove she was a viable candidate despite her disability. She suffers from a birth defect that caused her to be born without hands.

“A lot of the jobs that I apply for, there are certain things I can do, but there’s always that one thing that I can’t do,” Vandoorne said. “Sometimes I just wish people would let me show them all the things I’m able to do even though I don’t have hands.”

After Vandoorne got the job at the restaurant, she wanted to move out of her friend’s home, so she applied to live at the Hope House again. Despite having a positive experience when she stayed in the shelter previously, she says that there were pressures to leave quickly.

But sometimes when you’re homeless, people won’t hire you right away because you don’t have the proper clothing or you’re not super clean so it’s kind of hard to be rushed out of a homeless shelter. — Brittany Vandoorne

“Don’t get me wrong, it’s nice to have a bed and a place to go, but it’s stressful and they try to get you out as fast as possible,” Vandoorne said. “But sometimes when you’re homeless, people won’t hire you right away because you don’t have the proper clothing or you’re not super clean so it’s kind of hard to be rushed out of a homeless shelter.”

She stayed there for around two months before she was kicked out for arriving late during Coast Guard Festival. According to Vandoorne, the shelter had mentioned their strictness regarding rules like curfew but they allowed anyone who held a job to be a few minutes late, depending on their shift hours. However, she says they didn’t account for the heavy traffic that the annual celebration brought along with it.

“I was 10 minutes late and they were like, ‘You’re late for curfew, we can’t have you here, you have to leave right now, you have 30 minutes to pack up,’ even though I was working that night,” Vandoorne said. “I was a little stressed.”

Hope House said they cannot comment on specific cases but they do stress the importance of the shelter rules to all of its inhabitants.

Discouraged and out of options, Vandoorne moved in with her then-boyfriend.

“He just wasn’t the greatest for me,” Vandoorne said, her mood sombered. “I’d just sit on his couch and think, ‘I’m never going to leave this place and if I do, I’m going to be on the streets.’ It was really tough. I started to feel depressed about myself. Leaving him was probably the best thing for me.”

She suffered through weeks of feeling isolated, depressed and defeated when she got a message from one of her former-roommates from the Hope House.

“If my roommates had never texted me and asked me if I wanted to move in with them, I’d probably still be there,” Vandoorne said.

Laura, who is in her 50’s, was Vandoorne’s roommate from the first time at the Hope House and was the one that contacted her about the seasonal rental. Together they got in touch with Kelly, who roomed with Vandoorne during her second stay at the shelter, and Katherine, who was an Resident Advisor at the Hope House. Even though all three are more than ten years older than her, Vandoorne says that she thoroughly enjoys their company.

“Having people that have also had struggles too along side me make it easier,” Vandoorne said. “I’d say that now is the best I’ve been in a long time, probably two years.”

Although her current living situation is coming to a close and the uncertainty of where she will be in the coming months is looming over her shoulder, Vandoorne continues to focus on building her future.

“I actually really do want to go to college,” Vandoorne said. “It’s something I really want to do. My birth family didn’t go to college so I want to be the one person in my birth family that actually did something.”

She tries to keep her ambitions realistic, however.

SEASONAL SITUATION: Vandoorne poses on the front steps of her current home. She’s been staying there for several months, but as summer draws nearer, the pressure of finding a new home grows heavier on her shoulders. Vandoorne has been moving from place to place for two years, and is hoping that she will soon be able to find a more permanent apartment to live year-round.

“I used to have huge goals,” Vandoorne said. “I used to want to be a social worker and help people but college is so expensive and I don’t have that money and I don’t know when I’ll get that money. My goal is at least to get a full-time job and be able to keep that and live in an apartment. That’s pretty much my goal right now because my goals are so little since I know I can’t get to the biggest one.”

Despite having to keep her objectives small and the unpredictability of her living situation over the past two years, Vandoorne choses to see the good that has come out of her experiences.

“I believe that it is made me stronger,” Vandoorne said. “There are times where I’m like sitting there and I’m just thinking, ‘How am I going to do this, I’m not going to make it, I should just give up, I should just kill myself.’ But I’m still alive. I know how strong I am now because of this.”

Anna Wilson: The Believer

FAITHFUL FACE: Anna Wilson poses in an auxiliary room at Life Church. She attends the services there, as well as youth group.

Long brown hair frames Anna Wilson’s face as she flashes a bright smile directed toward the teenagers surrounding her. Life Church parishioners mill around the youth group room. The low chatter of mingling conversation hums, barely audible above the upbeat church songs that play in the background.

Wilson converses with her self-proclaimed “faith family” about struggles that had strengthened their relationship with their God. Although her belief is solidified now, there was a time where her faith was put to the test.

In eighth grade her mom had a stroke that affected her motor, speech and memory abilities. Because of that, she had a hard time holding a job and Wilson’s step-father became the main source of income for the family of four.

He held a laboring construction job and was often in physical pain, but he continued working. Despite the stressors of his career, he provided for his family until Jan. 5th 2012, when he died of a heart attack.

It was a typical day. After being dropped off at the bus stop, Wilson told her step-dad she loved him, and she would talk to him later.

She didn’t know that would be the last time she would see him.

With her step-dad gone and her family grief-stricken, 15-year-old Wilson was left to care for her mother and sister.

“It was really hard,” Wilson said. “I think the hardest thing was seeing my mom come crashing down, and my little sister, too. She was just running away from home all the time, my mom was just an absolute mess and I felt like I had to be the parent, I had to be the strong one.”

Wilson did her best to hold her family together, but because of her mom’s disability the bills quickly piled up. By Sept. 2013, most of their belongings were moved to a storage unit and she, her sister and her mother moved into the Hope House, a local shelter for the homeless run by Love In Action.

“There are so many worse places in the world,” Wilson said of the Hope House. “We were very, very blessed to have the situation.”

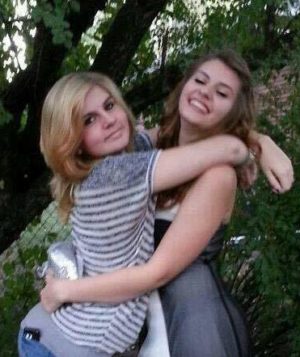

HAPPY FAMILY: Wilson, her sister, Emily, and her step-father, Chris, celebrate Emilys ninth birthday together in 2007

Although she acknowledges the positives of the shelter, she also says there were many hardships brought with it, usually involving school.

“[In the Hope House] we weren’t allowed to have electronics after 9, so they would take our cell phones and laptops,” Wilson said. “So, if I had a paper due, because I was trying to take AP Lang at the time, it wasn’t going to happen.”

Not only did she struggle to finish her school work, but because her mom’s vehicle was repossessed, she had no transportation to the high school

“When you’re 15 or 16, which was my age, you’re learning how to drive and stuff but I was just trying to make sure I could get to school because my mom didn’t have a car anymore,” Wilson said. “I actually wasn’t able to actually make it to school a lot, and a couple of my teacher started stepping up.”

Wilson recounts different high school educators providing aid to her, including John Mauro who drove her to school for a short time before helping her arrange different rides with more flexibility.

I think the hardest thing was seeing my mom come crashing down, and my little sister, too. She was just running away from home all the time, my mom was just an absolute mess and I felt like I had to be the parent, I had to be the strong one.

— Anna Wilson

Teachers weren’t the only people that aided and befriended her, however. According to Wilson, she made many connections during her six months at the Hope House.

“There was this one worker, her name was Jessica and she was probably like in her mid-twenties,” Wilson said. “Whenever I was stressed out about school or I had boy problems or anything, her and I would sit together on Saturday morning and just talk for hours.”

She also found friendship with a girl named Hope, who struggled with addiction. Wilson says that Hope had “the biggest heart” and would often listen to her rehearsing for chorale ensemble.

“I would go downstairs and shut myself in the bathroom [to practice],” Wilson said. “I’d come out and all the ladies would be in the basement sitting outside the door so they could hear me sing and [Hope] would always be there, in tears.”

Despite having unexpected companions in the shelter, like many teens facing homelessness, Wilson’s school social life struggled to survive.

“I just got so frustrated looking around hearing people complain about their boy problems, and their friend problems. and not getting the perfect dress for prom,” Wilson said. “They’re just these materialistic things. I started to feel really angry and I didn’t really want to connect with anyone and I shut everyone out.”

SISTERLY LOVE: Anna and Emily smile together before homecoming in 2012, while they were staying at the Hope House.

Wilson says that even though she knew her situation was not her fault, she was still ashamed of it, which caused emotional problems. Her mindset has since changed, however. She now speaks of her experience as enlightening, rather than disheartening.

“I don’t regret it,” Wilson said. “I mean, it’s been hard, but at the same time I’m so very grateful that I have had the perspective that I have.”

Wilson plans to take that perspective and become a social worker after she’s graduated college, which she will be attending in the fall. She credits much of her success to her faith in God.

“I’ve always been pretty deeply rooted in my faith,” Wilson said. “God has been my rock definitely. I’ve always felt like no matter how hard things are there will always be something better, something to look forward to.”

River Young: The Wanderer

Humidity and tension were in the air as screams echoed through senior River Young’s house. This summer, fights like these weren’t uncommon. Today was different though. Today was the day they had finally had enough of all the arguing. Today was the day Young left his home.

“Stuff at home was super rough all of a sudden,” said. “I guess you could just say everything was kind of like the snowball effect down the wrong way. Things just got super slippery and ugly really quick and I didn’t know how to handle anything.”

On the second day of August, River left his childhood home.

“We weren’t seeing eye to eye on anything whatsoever,” Young said. “When they told me to get out it was kind of just like to figure stuff out.”

While Young was struggling with his family situation, his friends were always by his side. He emphasizes the importance of keeping reliable friends near you in a tough situation.

“Totally just be yourself,” Young said. “Don’t take anyone else’s criticism. Just make yourself happy, do what pleases yourself. Find yourself a comfortable group of friends that you know will be there for as long as you need them.”

Two days after Coast Guard Festival, all the hype was starting to die down, and he decided to visit his parent’s house for the first time in a week.

“I was staying in touch with my parents, so we were trying to figure stuff out,” Young said. “Once we started seeing eye to eye again, we slowly started getting more in touch and I eventually came home to visit, see how everything was, and I ended up staying that night.”

Just make yourself happy, do what pleases yourself. Find yourself a comfortable group of friends that you know will be there for as long as you need them.

— River Young

His move out was difficult for not only him, but his parents as well. When he made the transition back into their home, they were happy to have him back.

“That break, in a way, was nice because once I came back and we figured stuff out, it was like we all kind of started back over, so we all could start where we left off, all clean,” Young said. “It’s crazy to say, but I feel clean. I feel so much better just about everything, like school, working, just everything.”

Although Young is in a good place in his life right now, things weren’t always so easy after he had gone through this experience.

“Coming back into school was hard,” Young said. “It was just hard to get back into the hang of things, feeling so off for so long. I was pretty much on my own there when I came back for a while.”

Through all the ups and downs, Young kept a positive outlook on everything he went through.

“I learned a bunch actually,” Young said. “It was actually a good time to figure out the real life on your own. It sounds weird to say, but it was kind of a good experience to figure that stuff out.”

Wendy Kuhlman: The Transporter

A little girl nervously climbs into the dark navy van with golden letters on the side spelling out, ‘Grand Haven Area Public Schools’. Seat belts are attached to the gray polyester seats, unlike the familiar blue leather of the normal school bus seats she’s been used to. As she buckles up, a smiling face turns around to greet her.

Van driver Wendy Kuhlman, or Miss Wendy, as the displaced children who she takes to school call her, has been driving the homeless van 200 miles a day, for five years.

Whenever a new student rides her van for the first time, she tells them the story of when she herself, was once homeless and living in her car. Every Tuesday and Thursday, Kulhman brought her son and daughter to Pottawattamie Park for a picnic. They were always curious about who lived in the house on the other side of the fence next to their picnic spot.

Today, Kuhlman lives in that house.

“I get goosebumps every time I tell that story,” Kuhlman said. “I try to tell the kids, ‘You may not know where your life is going now, but it may be right next to you.’”

Kuhlman became homeless when she grew sick and had to be hospitalized. This caused her to lose her job and condo. When faced with the option to move hours away to her family’s house, or stay near her kids who lived with her ex-husband, she chose to live in her car, near her children.

“That’s why I took the job, because I’ve been there,” Kuhlman said. “I know what they feel like. I kind of know what they’re going through, even though every situation is different.”

The five children that ride her van have had to move out of the district after losing their housing. There are four other vans, but Kuhlman has the longest route, driving all the way to Fennville and back through Holland to make sure these students get to school on time. She then drops them all off at the end of the day.

“It’s a very rewarding role, because sometimes they just need someone to listen to them and understand what they’re going through,” Kuhlman said. “It’s very rewarding. The kids are very grateful for their ride because what Grand Haven does, is they provide the ride to keep their schooling stable because their housing is not at the moment.”

The students who ride Kuhlman’s van range from kindergarten to high school age and go to Ferry Elementary School, Lakeshore Middle School and Central High School.

It’s a very rewarding role, because sometimes they just need someone to listen to them and understand what they’re going through

— Wendy Kuhlman

“They do not miss school at all,” Kuhlman said. “Nobody misses my van, very rarely the other ones either.”

Kuhlman heard about the job through her friend who was a bus driver. She told her that it would be the perfect job for her after experiencing homelessness herself.

“It made me a better person,” Kuhlman said. “I had a good job, a condo, I had a great life. It made me appreciate life every single day, and what other people are going through or may be going through. I’m a giving person anyways, but it made me more giving.”

When Kuhlman was first hired, there were only two vans. The amount of children needing the van has grown, as they’ve expanded to four. In Kuhlman’s opinion, they could have used five or six vans in the past couple of years.

“It’s not widespread talked about because families don’t talk about it, because a lot of times they’re embarrassed or feel bad,” Kuhlman said. “The children don’t talk about it openly a lot because they also feel bad. A lot of those times, a parent has lost a job or gotten divorced. Some of them have struggled with alcohol or drugs. We also have picked up foster kids who have been put in a foster home. They also ride the homeless van if it’s a temporary situation as well.”

Although all of these students come from different backgrounds, they share similar worries.

“I think the common thing is they’re not sure where they’re going to end up, or where they’re going to live or if they’re going to be permanently out of their school district the following year, because it ends up where their housing ends up,” Kuhlman said. “So a lot of them just don’t know where their lives are going to end up or where they’re headed.”

The 2016-2017 school year began with 187 living without permanent housing.

“A lot of us are not aware how many homeless people are out there in Grand Haven, and every situation is different,” Kuhlman said. “There’s not one that’s just like the other one either.”

Kuhlman is glad the van program exists, for the sake of the children.

“They would be jumping from school to school to school and never making any true friends, and never being able to put their feet in and dig into their education goals,” Kuhlman said. “They would be lost, they truly would be. My kids tell me thank you every day when I drop them off. It’s crazy, but they do.”

The goal of the van program is to keep students’ lives stable in hopes of them re entering into housing into the same district as their school and friends.

“Their schooling, all these students, I haven’t met a student who didn’t care about their grades or didn’t care about anything when they were homeless,” Kuhlman said. “They’re goal-oriented and they want to be able to get through those goals.”

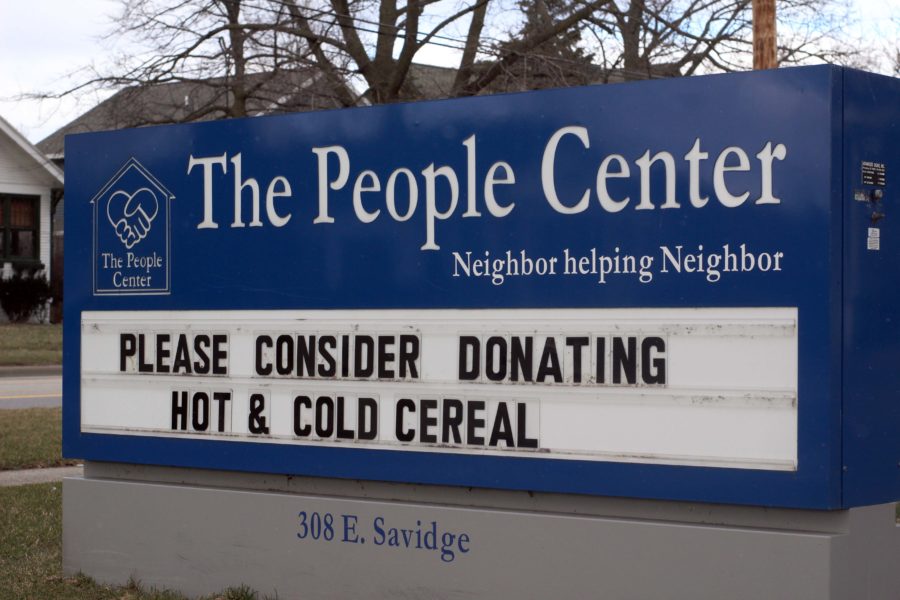

The People Center: The Starting Point

Karen Reenders sits at her office desk wading through credit histories and rental applications, struggling to find a home for the home insecure community members she serves. Reenders has been the Director of the People Center for 18 years, and every year she’s finding it more and more difficult to find permanent homes for families in need.

“If you don’t have at least one parent making really decent money, it’s hard to live here,” Reenders said. “It’s just a popular place, and it’s a tourist town and everybody wants to be here, so it’s hard for the clients to stay here. I’m finding that really has come to a peak over the past couple years. I’m having it harder and harder to move people on once they’ve been here.”

The People Center runs out of Spring Lake to provide housing for families who face some sort of a housing crisis in the Tri-Cities area. The clients must be working full time to qualify for the program. They are required to attend the Financial Empowerment Center through the City of Grand Haven to become mortgage and rental ready and can live there up to six months, rent and utility free. The intention is for them to meet their housing goals so that they can move on.

The center also provides food and clothing through donations to anyone who stops by and is in need. All aspects of the center bring out different emotions in people.

“They are stressed out, they are teary,” Reenders said. “It’s very emotional for them. They are at rock bottom. For the food and clothing, more grateful. “Oh my gosh, thank you. We’re able to feed the kids when they get home from school.” That kind of stuff. I see a lot of gratefulness with the food pantry. A lot of emotional stress if they’re applying for housing.”

It’s very emotional for them. They are at rock bottom. For the food and clothing, more grateful. “Oh my gosh, thank you. We’re able to feed the kids when they get home from school.” That kind of stuff. I see a lot of gratefulness with the food pantry. A lot of emotional stress if they’re applying for housing.

— Karen Rendeers

Every once in awhile, a high schooler passes through the center with their life turned upside down. While the People Center helps out students and their families as much as possible, sometimes all a teenager in this situation needs is a friend.

“I do see sometimes when we have high school age kids here, it’s the worst time of their life,” Reenders said. “They’ve just lost their housing, wherever they’ve been secure, and now they don’t even know what’s happening in their lives. They become upside down and they really need someone to go, ‘Hey, I get it. Come over to my house.’ Just be a friend, it would be really cool.”

Reenders believes that much of the housing crises happening in Grand Haven came about because of the decrease in housing that supports lower incomes.

With six apartments, the People Center can house 24 people at a time, only taking a small portion of the people who apply.

“It’s definitely a hidden issue here in our community,” Reenders said. “I think what causes it is not only the financial mistakes that the adults are making and continue to make, but also there’s no affordable housing here. We live in a really expensive community where they keep building but then the apartments are going for market value and my clients can’t afford it.”

Although homelessness isn’t often seen or talked about within our community, Reenders assures that it’s still happening all the time.

“Our hidden homeless, they’re not on the street,” Reenders said. “They’re not on the corners. They’re not down by the factories where the factory’s pushing out warm air. They’re sleeping three and four families in one house. All the friends are staying in one place. I think there’s no place for them to go like a big city. I think people take you in, in our community, before you have to live on the street.”