Bad breath(alyzing)

Current school breathalyzing policy has potential to conflict with the law and a fundamental civil liberty

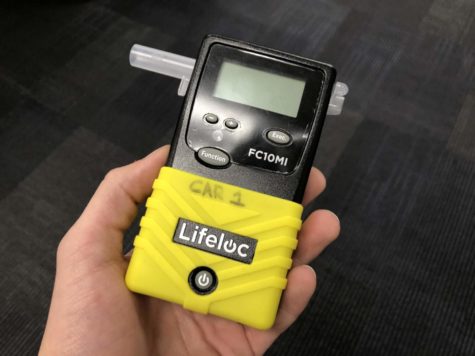

Public safety officer Dana Beekman holds out a preliminary breath test (PBT) to provide a firsthand experience of what it would look like blowing into the device. The legal blood alcohol content (BAC) limit for operating a vehicle is .08; anything higher and the person is considered drunk and it is illegal for that person to drive. Beekman says public safety officers have to wait around 15 minutes before they can even administer the PBT.

Senior Olivia Striegle strolls through the brisk autumn air, swings open the shiny, metallic doors to the athletic entrance and immediately becomes log-jammed by a thick line of people. But there is no cause for concern – this is typical for any high school dance.

As the line crawls its way to the tables, most kids fork over their tickets, display their ID and fasten their wristbands. Striegle does the same. However, she is asked for something else, something most students weren’t asked for.

A breathalyzer test.

“I was super nervous because I’m a worrier,” Striegle said. “I freaked out, what if there was wine in the chicken I had for dinner?”

She blows into the tiny gray nozzle. After a five-second countdown, a beep sounds. Is she above the Blood Alcohol Content (BAC)? If not, congratulations, she’s not intoxicated. Here, take the mouthpiece as a souvenir.

For Striegle, this was the first of the three total times she has been breathalyzed. She’s kept two of the mouthpieces.

With the issue of intoxication resolved, Striegle is finally able to enter the dance. Yet she’s left with a major question: why did they pick me?

She is now tagged for the night as the kid who was breathalyzed. She knows she has no reason to worry internally, except for the social impact.

“I knew it wasn’t a big deal because I wasn’t drinking and I don’t drink,” Striegle said. “But with everyone watching me I felt singled out.”

An invasion of privacy to some, Striegle’s case brings up a fair point: how does Grand Haven High School select students to be breathalyzed?

This is one of Grand Haven Public Safety’s breathalyzers and is just one of the many types available. The mouthpieces are removable, and GHHS often allows students whom they breathalyze at dances to retain the mouthpiece as a “souvenir”.

More important yet, is breathalyzing at school dances necessary? Deputy Legal Director for the American Civil Liberties Union of Michigan (ACLU) Bonsitu Kitaba thinks not.

“Breathalyzers show the school isn’t dedicated to solving the social issue,” Kitaba said. “They just want to scare students into not drinking.”

Striegle agrees, citing current social stigmas as a reason.

“I think everybody knows that illegal drinking happens,” Striegle said. “I feel like it’s accepted and it’s not a huge thing. They don’t make it as big as they probably used to. I know a ton of people who participate in this activity and it’s not a big deal to them. There are other things that are viewed as worse than drinking, like smoking.”

The numbers suggest otherwise. According to the Youth Assessment Survey from 2017 for Ottawa County, 32% of students admitted to having some form of an alcoholic drink in their lifetime and 13.1% admitted to smoking in their lifetime.

Additionally, according to alcohol.org, an American Addiction Centers Resource, “individuals between the ages of 12 and 20 account for 11% of all alcohol consumed in the United States”. By contrast, 5.5% of teenagers are smoking nowadays, per the Youth Assessment Survey.

The effects of having an above-zero Blood Alcohol Content (BAC) at a school dance are outlined in the student policy handbook. Each student is required to read the manual at the beginning of each school year.

Additionally, an academy class during homecoming week was allotted to reinforcing conduct and proper procedure rules at school dances with a supplementary lesson.

One of the points of the lesson was to alert students to the administration’s use of breathalyzers and their supposed purpose. They also emphasized the disciplinary measures a student invokes if their BAC is above zero.

“We want a safe environment,” Wilson said. “If kids choose to [drink], we don’t want them at our events. When they do, it puts us in a position where we have to deal with it – we can’t ignore it. We have a responsibility.”

She recounted the policy has been in place for nearly 15 years and was implemented because Grand Haven, as well as other area high schools, were having issues with students showing up to dances drunk. Wilson also said the school has not had a problem with wasted students in a few years.

When administrators choose to breathalyze a student, they do so “randomly”.

“We typically just pick a number between one and nine,” Wilson said. “From there, we just say ‘five’ and breathalyze every fifth kid, or ‘eight’ or whatever.”

Attorney Ed Sternisha, who specializes in cases related to drunk driving, sees the school’s method of selection as problematic.

“Random, to me, is concerning,” Sternisha said. “How are they determining who’s picked randomly? To me, that’s putting all the student’s names in a hat and pulling a set number out. So I don’t believe random selection is appropriate.”

While there is no proof to assert the administration was not testing randomly on the night Striegle was tested, it does bring up a fair point: is random selection the proper route?

Instead of a randomized test, Sternisha believes the school ought to pick students for a preliminary breath test (PBT) solely on reasonable suspicion.

“Perhaps reasonable suspicion is more appropriate,” Sternisha said. “When a cop stops someone, it’s because they have reasonable suspicion that they’re doing something.”

In that case, actions to ensure personal safety are warranted. It’s alternative motivation, Kitaba notes, that schools should be wary of violating.

“If the school receives a tip, or has observed behavior that gives them reasonable suspicion, then they should take steps to address the issue with that particular student,” Kitaba said. “When the test is random, it’s not based on any reasonable suspicion which makes it a suspicionless search, and those are not permitted.”

Wilson claims to be one step ahead of that curve. She understands what is at stake.

“I’m not naive to think nobody drinks,” Wilson said. “If we feel there’s a reasonable suspicion of someone drinking, and there’s something we can do, we’ll do that.”

Breathalyzers show the school isn’t dedicated to solving the social issue,” Kitaba said. “They just want to scare students into not drinking.

— Bonsitu Kitaba

The kinds of rights students retain from the street to the schoolhouse is something of a hot topic.

When looking at the Supreme Court in the instance of New Jersey v. T.L.O., the Court ruled that the Fourth Amendment applies to school officials, so long as the search is reasonable. Otherwise, students are justified in their legitimate expectation of privacy at school.

“A random breathalyzer test or searching every student’s locker without reasonable suspicion are the kinds of tests we as the ACLU would say do not abide by the Fourth Amendment,” Kitaba said.

In terms of Constitutionality, this is true. However, in the instance of breathalyzing at dances with reasonable suspicion, students are out of luck. They’re most likely not escaping a PBT anytime soon.

“Students have no right to a dance,” Sternisha said. “A right that the students should demand, though, is to make sure that whoever is administering a PBT knows how to use it, knows when to recognize when it’s not working properly and to understand the limitations of the device.”

Instead of stressing about being chosen to submit to a PBT at the next dance, or whether or not the device will read a false positive, Sternisha suggests students be asking administrators when the last time was the device was calibrated, or whether or not the administrators administering the tests have basic training to use and understand the devices.

Police departments throughout the state are required by law to calibrate all breathalyzers once every month to make sure the devices perform properly.

If a police officer administers a PBT on the side of the road to someone they believe to be drunk, that test cannot be used as evidence in a case to convict the person of drunk driving, even if the device reads higher than the legal BAC limit of .08.

“Random breathalyzers, in our perspective, are not going to address the issue,” Kitaba said. “You might have done nothing wrong and not had any alcohol and you might not test 0.0 on a PBT. That’s because those machines have error rates. We don’t want students who are doing the right thing to then be disciplined because of technology.”

Likewise, this means students do have the right to refuse to submit to a PBT, but if they refuse, that also means they don’t have a right to enter the dance.

“The Constitution and the Fourth Amendment protect every student’s right to privacy,” Kitaba said. “But the school does have certain rights as well to ensure that there is an orderly administration of education, orderly environment, and that it’s a safe environment.”

While it may be easy to say the policy has done its job, given the school hasn’t had an issue with students attending the dances drunk, one may wonder if it should remain in effect.

“I don’t feel like there’s a reason to spend time revamping the policy,” Wilson said. “It’s been effective and it serves its purpose.”

Yet, based on the policy and its implementation, students must ask themselves if they are being wronged or not. Kitaba, for one, believes revision is necessary.

“A policy should not be enacted ‘just because’,” Kitaba said. “It sends a message when policies like these are implemented: the administration doesn’t trust the students.”

A policy should not be enacted ‘just because’,” Kitaba said. “It sends a message when policies like these are implemented: the administration doesn’t trust the students.

— Bonsitu Kitaba

While this may be hard to hear for some, there is a solution. With the rule unlikely to change by itself, Kitaba suggests students take action for their desired reform.

“Students need to know that they don’t just have to sit idly by or let the administration to whatever they feel is right for students,” Kitaba said. “Students need to know what their rights are and be able to stand up for them. Because today it may be a small inconvenience, but tomorrow it could be a bigger intrusion.”

Senior Caleb Berko is embarking on his third and final journey around the sun as a member of the Blade staff, and he cannot wait to get underway. In his...

Co-Editor-In-Chief and senior Sam Woiteshek has begun his farewell tour in his final year at The Bucs’ Blade. Sam loves following the Michigan Wolverines...

Not Drew Edwards • Nov 27, 2019 at 1:58 am

Drew Edwards,

Please read me the line in the constitution that says minors have the right to drink…or for that matter anyone…I’ll wait.

Also what right was infringed upon when you were pulled over? Many people leave the downtown area from local bars after having a few too many. Was the cop being over cautious by stopping you? Yes. Did he infringe upon constitutional rights? I think not.

Drew Edwards • Nov 26, 2019 at 9:11 pm

I agree completely this is against our constitutional rights. I remember a few years ago in Grand Haven coming from downtown and a police officer pulled me over for no reason and made me take a Breathalyzer and couldn’t explain why they pulled me over of course I tested 0 but my rights were infringed upon as well. Should have followed up and wrote a letter to the supervisor of the police board but unfortunately I didn’t. I’m thankful that you are standing your ground I think this is a great noble and worthy cause.. well done