GHAPS leaders respond to parent group’s criticism of literature

Parent group is concerned about books in GHAPS libraries that they’d like to see placed behind the counter, severely limiting student access to certain titles

March 9, 2020

On Jan. 13 at the Grand Haven Area Public Schools Board of Education Meeting, a concerned parent, Jenifer Stuppy, brought to attention a list of books she deemed were “sexually explicit”. In particular, Stuppy took issue with One Man Guy and the supposed graphic sexual situations mentioned in it.

Stuppy recommended that the library create a system of flagging sexually explicit content (allowing parents input) and then devise a method where parents give consent. She believes sexually explicit books should be kept behind a counter unless consent is given.

In an attempt to investigate the controversy surrounding the issue, The Blade interviewed many individuals of relevance. They are: Mary Jane Evink, Executive Director of Instructional Services, Sarah MacElrath, White Pines Middle School and Lakeshore Middle School Librarian, John Siemion, GHAPS Board of Education President, Devin Schindler, a Constitutional Law Professor at Cooley Law School, and Katie, senior who is a part of the LGBTQ community.

The Blade reached out to Stuppy, who declined to comment, citing that she didn’t “feel comfortable using the same level of candidness about perverse content” because she felt The Blade reporters were still “students and minors” who would not be able to handle the nature of the story.

Why is it concerning to place books on a “restricted list” and behind the counter?

Devin Schindler: There needs to be a legitimate pedagogical concern. If they’re purely pulling them out because they don’t like gay people and the books are pro-gay, that is viewpoint-based discrimination that the Court generally doesn’t allow school boards to do.

John Siemion: Restricting access is almost like banning books totally. I do not agree with that. Restricting LGBTQ literature is against my principles.

Katie: I don’t think it’s entirely fair to put books behind the counter. That increases the division by saying these LGBTQ people are different and you need special permission to know about them.

Under what circumstances should the school district limit access to books?

Devin Schindler: It comes down to process and pedagogy. Before schools start yanking books out, they should have a process in place to make determinations. Assuming that is in place, it boils down to intent. Is the school choosing to take out all these books because they don’t like the viewpoint?

John Siemion: I’m not sure if keeping them behind a counter is a good idea or not. We’re not trying to be the literature police. I don’t want to ban books and, to me, I have no reason to put those books behind the counter. They should be out and available for the kids.

Katie: Some of the books were children’s books and kids should have the option to read them if they want. If kids are looking through the library, they’re only going to read it if they want to – nobody’s forcing them.

What kind of power or control should parents vs. the school district have in making decisions about literature?

Devin Schindler: The school boards need to have unlimited latitude to set the curriculum and determine their pedagogical goals. Parents have a liberty right to the care custody control their children. In the school setting, that is reflected by school boards. That’s why we have school boards. We let the parents make the final decisions on how their kids are educated.

Mary Jane Evink: We want to be approachable for parents, we don’t ever want them to not trust us. We appreciate community questions, feedback and input because we’re educating students. We would never attempt to parent any student because that is a sacred responsibility left to the caregivers of children. Our job is to provide balanced reading material that meets a variety of parenting styles.

Sarah McElrath: Our doors are always open, parents are always welcome to come in and look at what’s in our library. They can always log on to their child’s destiny accounts, see what their child has checked out, they can call and talk to me if they’re concerned about a book or some of the material that we have or don’t have available.

John Siemion: That’s a parent’s prerogative. I don’t fault her for that at all. To me, that is good parenting.

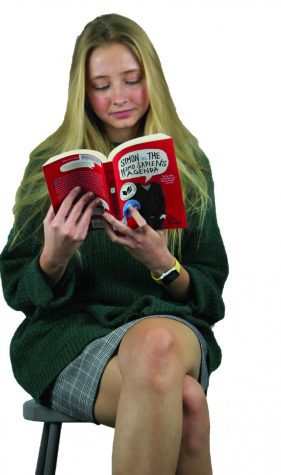

Senior Katie reads Simon and the HomoSapiens Agenda which was later produced into the movie Love, Simon. When Weigle was exploring her identity as a member of the LGBTQ community, she was able to turn to some of the literature at Lakeshore Middle School which helped her reaffirm her actualization and gave her a figurative mirror for her to look into.

What can be done for students so they better understand this content and that libraries are curated well to meet the needs of students?

Sarah McElrath: One of the things I start teaching students in fifth grade is that they can never unread something. I tell them, your parents aren’t always going to be there to tell you what’s okay to read, so you have to know what bothers you.

John Siemion: The media specialist is reviewing all books to make sure they’re appropriate for all grade levels. We have 6,000 students in our district so we have to meet a broad range of literature to meet the broad needs of our students.

Katie: The problem is when they only list LGBTQ books as being sexually explicit. That portrays a message, whether or not it was the intention, that LGBTQ people are explicit material. It puts kids farther in the closet.

What is the argument for including books that contain a variety of viewpoints?

Mary Jane Evink: We’re trying to provide books that have windows, mirrors and sliding glass doors. This means you want to be able to see yourself in the book. So, for instance, if you’re a person who has dark skin, you want to be able to read about people who have dark skin. We also want kids to be able to connect with other types of people so they develop empathy and understanding, like in the book Wonder.

Sarah McElrath: Everybody deserves to see themselves in a book. When I was in high school and started having suicidal thoughts, it didn’t make sense, I didn’t know what was going on, and I couldn’t ask my parents about it because I thought I was going crazy. To find a book about a character going through that, to put a name to it and to know that I wasn’t going crazy was huge. I think it would be the same way for someone who is struggling with their sexual identity or their gender identity.

John Siemion: I advocate for what is best for all students. Whenever someone is being denied rights, I see something wrong and I’m going to fight for it.

Katie: Parents try to protect their kids, but really, they’re just trying to push them into the closet because they’re scared of what will happen. That has to stop. Let kids make their own decisions

Is there anything else you’d like to add?

Devin Schindler: The woman could try to sue, but in my opinion, she would lose. The courts are going to give a lot of deference to the decision of the school board that these books serve a legitimate pedagogical purpose.

Sarah McElrath: I want to be transparent. If a parent has a concern or a problem with a book, I want them to know that they can come talk to me.

John Simion: We want to investigate thoroughly before we open our mouths. We don’t want to put our foot in our mouths. We can be blindsided by people who come to the board with things.

Katie: I feel like we’re going through a big cultural shift right now. There’s a lot of people that are fighting for things to stay the same as when they were teenagers. People should know that it’s not a bad thing. Grand Haven High School is super accepting, which doesn’t happen a lot of times.

Vincent • Aug 17, 2020 at 10:18 pm

I am a clinical, forensic, and health psychologist at a maximum security men’s prison and I empathize most with the children in this school district. I certainly would not send my children to this school. I highly doubt the reading material already approved by the school that these parents are referencing is truly inappropriate. The bigotry and ignorance in the forms of homophobia and transphobia from the parents trying to keep books from children, because they have LGBTQ themes and information in them is totally wrong, disappointing, and ridiculous. This should not be up for debate. I sincerely hope the parents with common sense about the truth regarding LGBTQ people file a legal injunction specifically against each of the bigoted parents for their disgusting actions as well as the school board for not immediately dismissing this clear, undebatable bigotry. If the school board succumbs to pressure and allows this bigotry to dictate children’s education, then I hope the other parents file a class action lawsuit specifically against each of the bigoted parents and the school board. They would have an excellent case and likely win.

There are countless valid and reliable research articles published in peer reviewed, scientific journals stating that homosexuality, bisexuality, and transgenderism are completely healthy, natural, and normal. Homophobia, however, is in fact a diagnosable mental condition in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5). This, of course, is also based on countless valid and reliable research articles published in peer reviewed, scientific journals. Is the Grand Haven school district catering to bigotry in the forms of homophobia and transphobia out of fear of confrontation with homophobic and transphobic people, because they happen to be a small group of parents? If so, then this is very concerning, especially from a legal standpoint and for the psychological well-being of LGBTQ children. LGBTQ children are currently approximately three times more likely to attempt suicide than straight children. This is not due to being LGBTQ. It is primarily due to being victims of homophobia and transphobia, such as that from these parents. This number has significantly decreased over time due to greater socio-cultural acceptance of the truth about LGBTQ people, accurate education, and mental healthcare. Furthermore, any parent who currently thinks their children are searching a library for inappropriate or misperceived inappropriate reading material of any kind further proves their laughably ridiculous level of ignorance. This sounds like a group of “Karens” who need a basic accurate education. The uneducated should not be allowed to dictate education, especially when their biased judgments are clearly based in bigotry.

Tina • Mar 10, 2020 at 8:55 pm

If your child is in high school and you have not taught them about sex or about all the different types of families that exist in the world, you have not done your job as a parent. You can fully expect other students to assist you. All the information in the world is readily available on the internet. Hate to break it to you, but kids aren’t looking in their local library for “scandalous” material. Perhaps people should busy themselves with checking their kids phones or computers.

Jeff • Mar 9, 2020 at 10:10 pm

Do you know which other goverment thought it would be best to push idealogies and ideas on kids that the parents did not want…Nazi Germany…just saying. Now before you jump all over me, consider that it is the parents right and perogative to bring up their children the way they see fit. Luckily we live in a free country where I may choose not to send my kids to a public school. Unfortuantly, for some parents that disagree with some of the things taught the only choice is the local public school, as a result, they will have little say in what their kids learn and the idealogies and moral values of others will be forced on their children. Many believe these parents are wrong for “sheltering” them or believe the children will learn it anyway, as though it’s the school’s job, and not the parents, to teach them everything about the world. It’s a school library for minors, yes, there should be a level of censorship. This is why I support a voucher program to allow parents to send their children to the school of their choosing. Maybe a better person to interview on the otherside of the issue would be someone like myself, who is not a part of the school by choice and does not have to worry about the “mob” within the school that disagrees with me.

Tracy Wittlieff • Mar 9, 2020 at 4:45 pm

This is incredibly well researched and written. I am so impressed with the level of scholarship presented here! Gen Z gives me a lot of hope for our future!