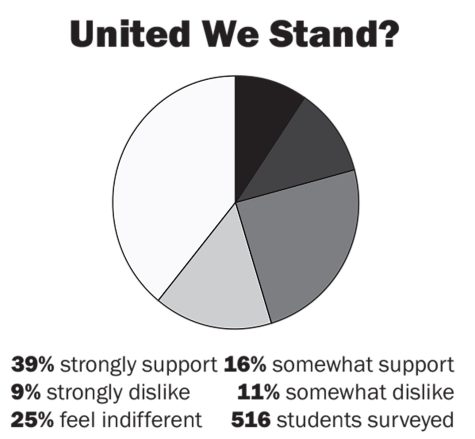

Patriotism, protest or peer pressure?

Students have differing opinions on standing for pledge

A Class Divided: Students in Mrs. Dean’s room stand for the pledge while some of their peers remain seated.

December 20, 2022

Every high school student knows the drill: zone out during morning announcements and wait for your cue to stand up for the Pledge of Allegiance. Some kids stand and say it enthusiastically while others follow suit without hesitation or passion, and some don’t stand at all.

This is typical. For many, the pledge is nothing more than a routine task at the beginning of each day, like brushing your teeth or checking your email.

In 2012, Michigan passed a state law declaring that an opportunity to recite the Pledge of Allegiance must be given every day in public schools, but that students should not be obligated or compelled to do so. While some students appreciate this opportunity to honor their country, others are less appreciative of the law and find it as an opportunity to protest.

“It means standing up for our country and what we should be,” junior Rece Madison said. “I am proud to be American. That doesn’t mean our country is perfect, but it’s a pledge to what we do in the future to make sure that’s the truth for our country.”

The Pledge of Allegiance was originally drafted in the late 1800s as an oath for unity, loyalty, and pride towards the United States. It wasn’t until 1954 that the words “under God” were added, making it the iconic 31-word statement we know today. The phrase was added during the second Red Scare as the rise of communism frightened many Americans. President Eisenhower felt the nation needed a stronger unity against Russia and turned to Christianity.

However, some students see this as the problem.

“I think it infringes on the separation of church and state,” said senior Avery Rant, who does not stand for the pledge due to religious objections. “I don’t have a religious affiliation, so I don’t want to say that. It’s limiting to people and it doesn’t apply to everyone.”

Religion in public schools is strictly banned under the ideal of the separation of religion and the government with the First Amendment’s establishment clause prohibiting religious practices in schools, even if students are not required to participate. In the 1943 case West Virginia v. Barnette, the Supreme Court ruled that students cannot enforce a unanimity of opinion on any topic, including patriotism. However, the words “under God” in the pledge have not yet been addressed in court – it seems to be flying under the radar for now.

Religion isn’t the only objection Grand Haven High students have to the pledge. Senior Abby Dzikowicz finds a problem with a different phrase.

“We say ‘liberty and justice for all,’ but that’s not true,” Dzikowicz said. “I don’t want to pledge my allegiance to something that’s false.”

Another traditional perception of protests against the pledge is that it may be disrespectful to those who serve our country. Many people, including Madison, stand in honor of veterans and active military members.

“I say the pledge for family members who have served or for people that currently serve our country, have before, or will in the future,” Madison said. “If you have a valid reason to sit, I respect it, but I don’t like the excuse of ‘I’m tired.’ That’s lazy to me, and that’s when it’s disrespectful.”

Rant disagrees, arguing the pledge isn’t about military service.

“The pledge is more political,” she said. “As we look back, do we really have those same fears [as when it was created]? Do we still need to pledge ourselves to our nation? I respect veterans in ways other than the Pledge of Allegiance,” she said. “Like with the national anthem. That’s happened forever; it’s meant the same thing forever.”

For those who see the same meaning in the pledge and the national anthem, it can be frustrating to see such differing levels of respect.

“I find it hypocritical when the same person who thinks it’s un-American to kneel for the national anthem is paying no attention to the pledge,” said Philosophy, U.S. History and AP World History teacher Kevin Howard.

When it comes to schools, it seems these 31 words have a different meaning for everyone – and for some, they have no meaning at all. It seems that saying the Pledge of Allegiance has been a habit since elementary school, and people often go through the motions without thinking about the meaning.

“It wasn’t something I thought about,” Madison said. “It shouldn’t be just a habit. It should be something we’re actually thinking about.”

Howard agrees.

“I don’t think it has patriotic value to tell kids to stand up and say some words they’re not actually thinking about,” Howard said. “So many kids are seated out of apathy.”

Regardless, a common theme expressed among students is the right to do what you choose and still be respected for it.

“I always want to have an open mind to other peoples’ opinions,” Dzikowicz said. “Everyone has different experiences and they should be respected.”